Wellness is a $6 billion dollar industry in the United States with more than half of all employers with at least 50 employees offering programs to improve the health and well-being of their employees. This figure, however, pales in comparison to the more than $990 billion spent on employee health insurance in 2014 and the $343.8 billion in out-of-pocket expenditures by employees in deductibles and contributions to their own health insurance.[1]

With such a large expenditure on a single line item, one would expect that employers would be devoting more resources to reducing that cost through wellness and other programs rather than simply shopping for the cheapest coverage plan. One possible reason for the relatively paltry sums spent on wellness relative to the overall insurance cost may lie in the way these programs are evaluated, with an overemphasis on short-term ROI.

Limitations of ROI as an evaluation mechanism

The criteria for evaluation of most corporate-sponsored wellness programs relies on the return on the investment (ROI) from that program. There are, however, limitations to that approach that may unintentionally skew resources that favor the higher short-term ROI relative to other programs. Indeed, a RAND Corporation study produced just those results- the returns were $3.80 for disease management (short-term) but only $0.50 for lifestyle management (longer-term) for every dollar invested.[2]

The long-term lifestyle management results are based primarily on a modest reduction in absenteeism but fail to account for the avoidance of cost in terms of expenditure for employees who do not get sick, or any reduction in insurance company premiums from having a healthier workforce.

A more realistic, and possibly less common, method of measuring returns on investment for different programs should adjust the calculation for the time horizon over which the program could reasonably be expected to produce results. This should also capture the lower healthcare costs for employees who do not get sick.

Moreover, it should factor in leverage that corporate purchasing power can wield by virtue of being a large buying group. This may produce consistently higher returns over an extended time horizon that traditional ROI calculation methods would not capture. These costs can be quite significant; it now costs $10,000 or more per person annually to treat someone with diabetes than someone who doesn't, according to an analysis of large insurance company claims data.[3]

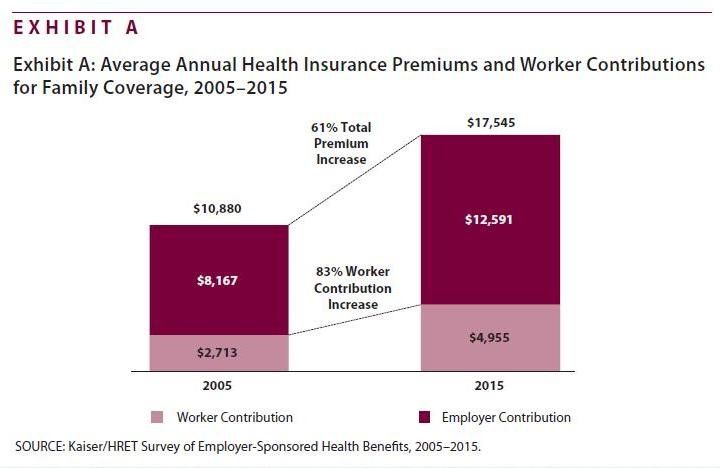

Employer/Employee Health Expenditures

Since 2005, employer-sponsored health coverage for family premiums have increased by 61 percent and the employee share of this cost has risen by 83 percent, placing increasing cost burdens on employers and workers.Corporations and insurance companies are shifting an increasing share of these costs to the consumer through:

- Higher premiums and higher deductibles for treatment

- Higher co-pay for prescriptions

- CDHP- Consumer Directed Health Plans

- Health Savings Plans

Additionally, the Kaiser Family Foundation has found that four out of five workers who receive their insurance through an employer have deductibles that have climbed from a yearly average of $900 in 2010 for an individual plan to above $1,300 in 2015, while employees working for small businesses have an even higher average of $1,800 a year.

One in five workers has a deductible of $2,000 or more. Since health insurance coverage is part of an employee's total compensation package, it is doubtful whether ROI measures are even used to assess their effectiveness.

Indeed, the main impact on employees is to reduce the salary component of their compensation by the employer's cost of providing health insurance ($12,591) and further reduce that amount by the worker contribution to their own health insurance ($4,955). Then the employees own after-tax salary is further reduced by the out-of-pocket deductibles (c $1,500) they bear before receiving any reimbursement.

Costs of Chronic Illness- e.g. Diabetes

Preventing the onset of serious illness can lead to significant savings over an extended period. Take just one example, diabetes. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) currently estimates the total costs of diagnosed diabetes at $322 billion, up from $174 billion in 2007, when the cost was last examined. In addition, more than 83 million Americans have pre-diabetes.

A study, Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2012 [4], addresses the increased financial burden, health resources used and lost productivity associated with diabetes in 2012. The discounted excess lifetime medical spending for people with diabetes was $124,600 ($211,400 if not discounted), $91,200 ($135,600), $53,800 ($70,200), and $35,900 ($43,900) when diagnosed with diabetes at ages 40, 50, 60, and 65 years, respectively.

The Health Care Cost Institute, a Washington-based group says that spending per capita on health care for people with diabetes was just shy of $15,000 in 2013. By comparison, $4,305 was spent in the same year on people who didn't have diabetes.

Costs of Lost Productivity and Absenteeism

The Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index surveyed 94,000 workers across 14 major occupations in the U.S. Of the 77 periods of workers who fit the survey's definition of having a chronic health condition (asthma, cancer, depression, diabetes, heart attack, high blood pressure, high cholesterol or obesity), the total annual costs related to lost productivity totaled $84 billion.

According to the survey, the annual costs associated with absenteeism vary by industry, with the greatest loss occurring in professional occupations (excluding nurses, physicians, and teachers).Clearly, chronic disease, absenteeism, and lower productivity costs take an enormous toll on the corporate workforce and ultimately affect competitiveness.

ROI Measures for Health and Wellness Expenditures

Today, 70 percent of employers use incentives to drive employee commitment, yet more than half do not know the related cost savings or relative return as it pertains to improved health.[5]

Access to Health Information

Despite more than $29 billion in financial incentives to healthcare providers by the U.S. government to convert to electronic health record systems, limitations in interoperability mean that only 20 percent of systems can exchange patient information with each other. Federal money, while well intentioned, was offered without stringent conditions and has led to the creation of information silos.

Many consumers struggle to obtain their own records despite a federal requirement for the provider to produce electronic copies within 72 hours of a request. Furthermore, many providers or their IT companies actively block or make it difficult to obtain records.[6] The consumer is the primary actor in the healthcare system since he or she bears the full cost of providing healthcare, whether through reduced wages, own contribution, out-of-pocket deductibles, and taxes.

Hence, the consumer is the only one truly motivated to change the status quo and thus can be the catalyst for change. The environment of escalating costs, inadequate security of provider EHR systems, and the lack of interoperability is forcing consumers to take matters into their own hands. According to the Surescripts Survey- Connected Care and the Patient Experience, 2015:

- 29 percent of consumers needed to physically bring records from one doctor's office to another.

- 40 percent said they had difficulty accessing their records and very few believed they would be able to obtain records within 24 hours.

- 55 percent of those surveyed reported that their medical history is missing or incomplete when visiting their doctor.

The implications of inadequate, incomplete or inaccurate medical records were estimated in a recent study published in the British Medical Journal and is demonstrated in the diagram below. If the medical error was a disease it would rank as the third leading cause of death in the U.S. and current reporting systems do not capture the true number of preventable deaths. Medical error is not reported on death certificates.

Sources of Health Information

The healthcare industry is undergoing a profound shift in the way care is provided and the location of that care. The points of care are more widely dispersed than the traditional settings of the doctor's office, clinic, or hospital. It is already possible to obtain flu shots, blood pressure readings, and visits with nurses at pharmacies or minute clinics. It is also possible to book appointments with doctors or specialists online and choose an in-office or virtual visit.

And modern smartphones increasingly have a number of features that can help measure, pulse, blood pressure, blood sugar, and other key indicators of health. Those functions coupled with consumer health devices that interact with smartphones (blood pressure cuffs, wireless scales, blood glucose meters, etc.) produce an ever increasing amount of data on an individual's health.

The sources of health information are increasingly scattered, and now, more than ever, the need to have comprehensive and accurate health information is critical. This has important implications for corporate benefits programs and administrators.

A Forward-Looking Approach

Modern mobile digital devices and tools are making it possible more than ever before to manage all aspects of modern living and only now are in the beginning stages in the healthcare industry. Benefits providers need to have additional components in their programs to increase the likelihood of better health outcomes for employees and their families. There should be a heavier focus on empowering employees to manage their health rather than being passive recipients of their healthcare.

- Support programs that give employees the ability to collect and manage health information for themselves and their families rather than relying completely on health providers. Tools that encourage transparency in health care costs, provider quality assessments and collection of information from more widely dispersed points of care and the proliferation of health devices would effectively provide the dashboard that consumers need to take informed decisions.

- Employers should consider having a discretionary health budget for each employee that supports the purchase of health devices, apps, and subscription services that equip the employee with the right information to proactively drive their health toward better outcomes. These programs will probably not show immediate measurable returns but in the context of the overall costs of employer-funded health plans, the cost is insignificant.

- Refocus evaluation of wellness expenditures away from the strict ROI measures and toward an appreciation of the quantifiable savings from not contracting a chronic illness, i.e. the avoidance of additional annual expenditure for employees who would otherwise develop chronic illnesses without effective tools to measure and change their behavior.

Supporting or sponsoring modern digital tools as part of an employee benefit program will benefit both employers and employees in a number of ways:

- Sense of control- empowerment

- Better informed consumers

- Fewer healthcare visits

- Better health outcomes

- Lower absenteeism and higher productivity

And having access to and effectively managing multiple sources of their own health information would put the employee in the information loop and could produce additional gains in the form of lower overall costs through a reduction in unnecessary testing, and fewer medical mistakes.

Continuing to focus on simple ROI metrics to measure effective of wellness programs could lead to skewing of resources toward existing chronic conditions or at best discounting the longer term impact of not contracting a serious and ultimately chronic illness, not losing time to absenteeism, and recapturing lost productivity. Though difficult to assess in the short-term, the longer-term benefits are clear.

Lower long-term health costs and thus lower premiums. According to an Aon Hewitt talent survey of senior HR professionals about their top concerns, 31 percent identified the retention of top talent[7]. For employers hoping to attract and retain skilled, qualified employees, a robust employee benefits program that incorporates long-term wellness incentives will yield a happier, healthier workforce and ultimately lower costs overall.

About the Author

Kevin Power is the Founder and CEO of The Good Health Group, which provides health management tools to consumers and to employees through HR benefit programs. He has more than 30 years of operating and Board of Director experience in telecom, IT, and software with both public and private companies. Learn more at: www.thegoodhealthnetwork.com

Works Cited

[1] National Health Expenditure Projections 2014-2024, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

[2] Do Workplace Wellness Programs Save Employers Money?, RAND Corporation, Jan 2014

[3] Health Care Cost Institute

[4] The Lifetime Cost of Diabetes and Its Implications for Diabetes Prevention, Diabetes Care 2014, September.

[5] Aon Hewitt 2014 Health Care Survey

[6] Report to Congress 2015

[7] Aon Hewitt 2014 Health Care Survey